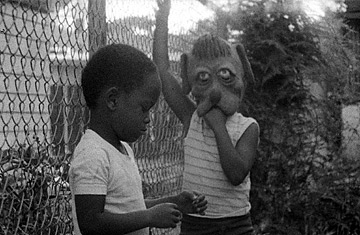

Angela Burnett (right) in Killer of Sheep, 1977

1977; Writer-Director: Charles Burnett

With Henry Gayle Sanders, Kaycee Moore, Angela Burnett, Jack Drummond

Milestone Video / New Yorker

Available Nov. 23, List Price $39.95

America was no land of opportunity for most of the black people living in the Watts section of Los Angeles. Decades of civic neglect, and the scars of the 1965 riots, had left the neighborhood looking like its own Beirut or Fallujah. Yet family life went on in the mid-70s, when this beautiful film was made there by Burnett, a Watts resident and student at the American Film Institute. This was his thesis film, and it's up there with Badlands and Eraserhead as one of the uncompromsing visions of the movie 70s.

Unlike the Terrence Malick and David Lynch movies, Killer of Sheep was not quickly released and instantly acclaimed. It became one of those films that are renowned but virtually unseen. Not until this year did Killer achieve a theatrical release, and critics agreed the movie lived up to its legend. Now comes a full Burnett DVD package, which includes another feature, My Brother's Wedding (offered in the 1 hr. 58 min. original version and a 2007 cut that's 38 mins. shorter), and four shorts spanning nearly four decades of this film master's furtive career. (Best is the 1969 Several Friends, a rough draft for Killer.) Only his wonderful To Sleep With Anger in 1990 and the 1995 cop drama, The Glass Shield, had a chance to reach audiences.

Stan (Sanders) works in a slaughterhouse. His wife (Moore) is at home with their young son (Drummond) and daughter (Burnett's own child Angela). Neighbors drop by to chat or to propose that Stan join them in a criminal enterprise. Stan and a friend buy a junky motor for their car, and the two men and their families go on a brief jaunt before the car breaks down. That's about it, for the plot. But the strength of Killer is in the details of a man, his family and his neighborhood. Burnett made his film in reaction to the blaxploitation movies, depicting African-American males as dope-dealing supermen. His take is also miles from the liberal Hollywood dramas that apotheosized blacks as noble overcomers. The view in Killer of Sheep is rigorously unsentimental but acutely sensitive. Burnett trusts viewers to see the characters as he does, sympathetically and without judgment.

The movie is a string of vignettes. Boys practice their fastballs hurling small rocks at passing freight trains. Watching them is Stan's daughter, her head hidden in a bloodhound mask; she sucks her thumb through the mouth hole. Stan silently goes about his work in the slaughterhouse. The heavy-set white woman who runs a convenience store tells Stan he should come work for her — in the back room. Now the boys' playground is a construction site, or maybe a destruction site. In Watts, it's hard to tell. They are seen crawling from the hole in the side of a house, jumping from one roof to another. Or they'll do a handstand on Stan's tiny porch and rest their feel against the wall. Women tease their men, and the men go out. They try moving a washing machine, and keep working on the damn motor. At night you hear the sound of crickets, a barking dog, a car's rasping engine. And throughout the film, a kind of Greek chorus soundtrack of blues, chanting misery, aspiration and the need to cope.

At the center of the non-action is Stan, a quiet man who may be either clinically depressed or just ground down, worn out and fed up. He has his moments of romantic reflection, as when he holds a hot cup of coffee to his cheek and tells a friend, "Don't it remind you of when you're makin' love how warm her forehead gets sometimes?" (The friend, laughing hard, replies, "I don't go for women who got malaria.") But he's lost the passion for his wife, who can't help wondering what's wrong; she stops in the middle of cooking to examine her face in the "mirror" of a pot lid.

Later, in the living room, Stan and wife slow-dance to Dinah Washington's "This Bitter Earth." She caresses his body, paws it, as he noncommitally keeps his hands on her thighs. When she passionately kisses his chest, he extracts himself and leaves. Standing alone, she picks up daughter's tiny shoes. The scene is elliptical, no loving or angry words spoken, but it's a heartbreaker. Toward the end, the wife whispers to Stan, "Let's go to bed." He does nothing, and the wife moves away a few steps. His daughter comes to him, and he lets her caress his face while wife watches.

These snapshots — of a man in emotional apathy or exhaustion, a woman who must feel she's a widow — aren't about black people. Just people, their needs and desperation revealed in the behavioral poetry of performance and a simple camera style. Killer of Sheep may be heralded as a document and testament of black cinema, and it is that. But it's also a tender, searing evocation of hurts that can't be expressed, little dreams that won't die.